“I looked at the picture of one of the bombers expecting to see a monster but, I didn’t see a monster. What I saw was a young man” – Gill Hicks. Survivor of 7/7 …

Today many will be remembering the lives lost and rearranged on the morning of 7 July 2005. I have.

The events of that day confronted us with many things. Horrific events like that do, and repeatedly.

The reminders of that time will, for many, occur in the context of anniversary remembrance, news footage which with the passing of years get shorter and shorter. For those who lives were rearranged on that day the concept of an annual anniversary is often meaningless. Each day, and for some, each moment holds a myriad of anniversaries. Traumatic loss in its many forms tends to have that effect.

Collective traumatic events, as indeed 7/7 was, one way or another insert themselves into our memories and remain. Whether the anniversary effect is moment by moment, daily or annually we will be remembering. ‘Who we will be remembering’? however, is an important question, so obvious, so assumed in fact, it seldom gets asked and in the not asking misses the point that memory is highly selective.

Selective memory is often defined by acceptable memory. Some memories we allow and are allowed, whilst other memories are banished, not allowed, not deemed accepted or wanted. The memories of 7/7 are one such example of acceptable and unacceptable memory.

The acceptable memories of the day are literally set in iron in the southeast corner of Hyde Park. Here 52 people have been named, memorialised into cast iron pillars. It’s a powerful setting and a powerful statement. But it is partial, it is incomplete, it does not tell or symbolise the full story and does not give permission for the full story to be remembered. In the later sense it is an edifice to banished knowledge.

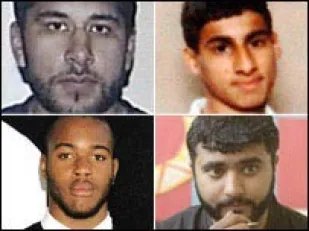

The invitation of the memorial to remember extends only to 52 who died and not to the whole figure of 56. The names of Habib, Germaine, Mohammad and Shehzad are missing. The message is clear there are those we are allowed to think about and those we are not, must not. We must not think about the four young men who birthed 7/7 and the way it rearranged life. Equally, we may say defiantly ‘but I don’t want to think about them’ .

The exclusion of the four young men from the symbolic memorial is symbolic in itself. I get the varied reasons for this exclusion, but the meaning causes me difficulty to say the least.

When thinking about something or someone is not allowed, if we ourselves make this choice, it marks the beginning of exclusion, a splitting off, a fragmentation. When applied to a person, to people, it creates ‘other’. Truth is, in the context of Habib, Germaine, Mohammad and Shehzad, it was the creation of ‘other’ that birthed 7/7 into reality.

The process of making ‘other’ is a process of creating ‘less than’. It’s the process of objectification. The reduction of person into object. If we want to understand why and how 7/7 happened in first place, in those six words, there we have it.

Crimes of all sorts are commissioned because in the mind of the perpetrator they have consciously or unconsciously engaged in a process of division and of reduction. The ‘other’ quickly becoming ‘less than’ making anything possible. It’s not a question of ‘who’ is being killed? but ‘what ‘is being killed? In the mind of the one who’s doing the killing they are killing ‘something’, seldom is it a ‘someone’.

This is not a process unique to those who go on to enact such a process of objectification individually. Governments, organisations, communities, rulers etc do it all the time. Approve it all the time. The creation and use of the very term ‘terrorist’ a prime example how the State operates on the dynamics of objectification, findings ways to legitimise the treatment of others as less than and enshrining laws that make it ok for them to objectify but not for others. This process can be referred to, understood and witnessed time and time again in world over the dynamics of oppression.

If the process we follow is one that results in objectification, then, State, Religion, Politics or indeed our own mind then the consequences are likely to be the same. We are all in peril.

So, what to do?

Let’s be clear, the process of all that unfolded on 7/7 began in the mind and it is to the mind where we must go if any different process is to be given a chance. We need to be able to invite our minds to start to comprehend its understanding of the very antidote to the process of objectification, that antidote being the process of wholeness. Easier said than done. More so because our understanding of wholeness is often deeply flawed.

If 7/7 made anything clear it was that we live in a culture of dividedness and fragmentation of the self. The very opposite to wholeness. When we contemplate what it takes to live a peaceful life, we extol wholeheartedness and a version of wholeness that is only constituted of all the perceive to be good. But being wholehearted, being whole, is only sufficient if your heart is your whole self; being whole is only sufficient if your mind is all you are. We are, of course, so much more expansive than our hearts and our minds or whatever fragment we choose to fixate on. But we compartmentalize our experience in this way, divide it into fragments, as if to divide and conquer it. We banish ‘bad’ and delude ourselves that only ‘good’ has a place if we are to be whole. We could not be more wrong.

By its very nature wholeness is the coming together of all that we banish in the name of ‘badness’ with all that we embrace in the name of ‘goodness’. It is the unification and acceptance of this paradox which takes us unto wholeness and prevents process of ‘othering’, splitting, making less than, objectification and all that follows in its wake. The 7/7’s of our world.

On this day of remembering there are of course those who knew Hasib, Germaine, Mohammed and Shehzad. They knew them before they became victims of the process of objectification. They knew them with fuller lives that were not reduced to a piece of media print, and some, if not many would have known them with the human capacity for love as well as hate. They may not have a column of steel erected in their memory but as members of the human condition they were not immune from attachments and all that lasts from such a sacred fact of life.

Banished thinking and banished knowledge may make us feel comfortable with ourselves. Being selective with the lives we choose to remember may make us feel right and just. But unless we start to recognise what it is that gets repeated in this then the cycle of 7/7 we will surely need to repeat. Remembering what less than wholeness looks like, will only serve us well if we can bare to remember what wholeness actually is.

Br Stephen Morris fcc