For over a decade I found myself at the heart of a particular suffering which was far outside the acceptance of many. At the time Ireland was going up in smoke and its people living in England became the target of politically informed oppression and hatred. The resultant suffering of those involved was one that no one wanted to know. In the divisions that characterised those times, fear reigned. As is with any experience of oppression, the need to survive meant for many that much of life and particularly life’s suffering becomes secret and hidden.

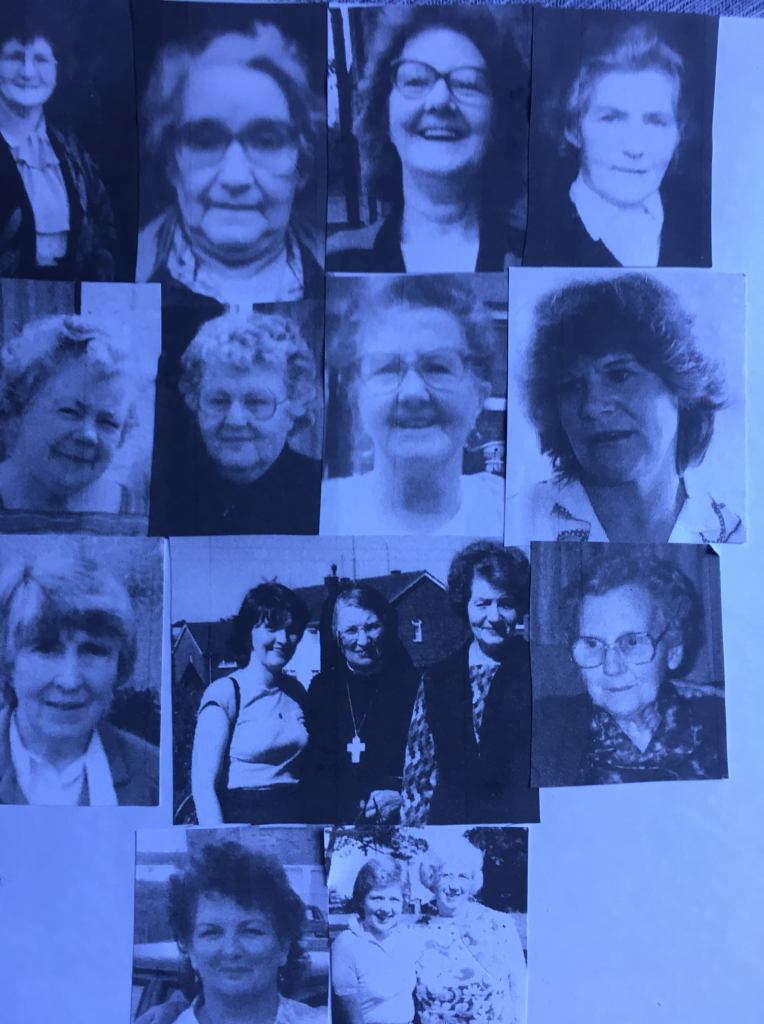

I am unable to remember this time without recalling the many mothers of prisoners I have had privilege to know across decades of my work. Mothers were at the centre of this war visited upon them by the English governments. They were not in the news, they were hidden from sight but, they were there.

In the early 80’s, I and many others witnessed the depth of agony as ten mothers watched their sons of Ireland die on hunger strike at the hands of the British state. Torture.

Then there were the mothers I stood with in the Old Bailey over the years that followed. Witnessing them as they looked across at their sons and daughters receiving sentence in the dock, exiles in a foreign land.

Closer still, there were those mothers too who filled my home and my life whist they endured the wait for freedom of their children, imprisoned until the miscarriages of British justice were laid bare. All of these mothers I remember. The first photograph in this post is of some of those mothers.

The other photograph in this post is of an almost life size statue of another mother, The Mother of God, Mary. Our Lady. She lived with me across those years and still does. This beautiful French statue has over time observed many moments of despair meeting with moments of hope. I know that because her feet are covered with lipstick! The lipstick kisses are from those decades I now recall, when Sr Sarah and I provided a home for the many relatives of Irish prisoners during their visits to loved ones in the British goals. During those years, if you were Irish in Britain at this time you were outcast and, much like with the Muslim community now, no one wanted to know. It was in this context that ‘Our Lady of the Lipstick’ as I now call her, came to symbolise so much.

The lipstick kisses remain as a symbol of those dark years and in particular indicate part of the story that is seldom recognised or told. As with the loved ones of most prisoners’ families, their story is characterised by despair and hope. I would see such etched on the faces of the mothers and wives when they would arrive as complete strangers on my doorstep. Many of them had suffered the humiliation of ‘guilt by association’ manifest in detention at the ports, strip -searches, harassment and racist abuse by the bucket load. Their fear was manifest across the few days they would stay with me. The despair of the present and of the future, what would become of their loved one? and indeed what would become of them? These were the questions behind every thought and word they uttered. But in all of that, the kisses to Our Lady still occurred and over the years her feet slowly became covered in the kisses of despair and hope.

As is so often in the stories of humanity, the raw experience of paradox reaches deep into our being and takes us, despite our protest, into territory far from any comfort we have ever known. Many others in our world are in such a place right now. Many without a cultural or spiritual resource of resilience to call upon and no feet on which to place kisses.

But regardless of lack of resource, regardless of lack of resilience, all experiences of paradox provide, if we dare to go there, a space of middle ground. The coming together of seemingly polar opposite experiences create, at their very meeting point, something different and it is often exactly that space where we need to go. It is in that middle space where resource is to be found.

The space created by the paradox of despair and hope we can call – acceptance.

Trauma, be that of a Irish prisoners relative in the 70’s and 80’s, the trauma induced by a virus in 2020 or a war against evil in 2025, provide to all those involved experiences of despair and hope.

Despair and hope are the defining features of specific trauma. I was privileged to gain a clinical specialism year at the Tavistock Clinic Trauma Unit many years ago. My mentor, Dr Caroline Garland, taught me that in response to traumatised clients our task was the re-installation of hope. When life experiences have eroded the supply of hope, like a mineral, it requires the right environment, care and attention to enable it to grow again. Her powerful analogy has stayed with me and is a constant reference point for me, not only in relation to my clinical work but in all areas of my life and in my connection with others.

Throughout life there is always much need for the re-installation of hope. We all need to work hard in the transformation of our own and others despair into hope. The process can and in many ways must start now and as indicated, it starts often by going, screaming and kicking maybe, to the place of acceptance, the acceptance of now.

It often would seem that we are afraid to hope. I know for sure that the kisses of hope planted on the feet of Our Lady were made in deep anguish with many tears. Such a place is where we come to acceptance, it’s never easy and what follows is unique for us all. But what I also know for certain is that the place of acceptance is always, always, always the place of peace. Even though we may not know that at the time.

Br Stephen Morris fcc