I have again been reading about ‘Ghosts from the Nursery’. ‘Ghosts from the nursery’ is a powerful concept I was taught early in my forensic training. The theory has stayed with me, remained in my thinking and its reality has been witnessed by me in most people I have worked with almost every day since.

‘Ghosts from the nursery’ refers to the fact that we all carry within us the influence of at least three previous family generations. In the consulting room, prison cell, investigation room, secure ward and indeed in our own place in the world the crucial question to all is ‘What do you know about your Great Grandparents? Grandparent? Parents?’

In forensic settings for those who have murdered the question has a particular poignancy. Often made more explicit when the follow-on question is asked; ‘Who were you killing?’ In the unconscious mind of the person who has killed, their victim is seldom the body in front of them.

My first clinical supervisor prepared me well to ask these questions and to explore beyond the first answer. When discussing the latest assessment with someone who had murdered, she also always instructed me to remember ‘Ghosts from the nursery’. She would say, “Remember Stephen they were once a baby in a mother’s arms”. A strange thing to do when a 45-year-old is sitting opposite you. But as she predicted, over time the answers to my questions always came and the impact of knowing always worth waiting for. Such conversations have revealed to me, time and time again along with everyone else, the murderer also asks, why?

The mind of the murderer, unless shaped by psychopathy and only very few of those who murder can be considered psychopathic, is no different to yours or mine. When confronted with parts of themselves they would rather not know, they too want to know why. There is something deeply human about that. To answer such a question they, we, I need to feel safe, be safe. The walls of the prison, secure hospital, secure unit may remain, but they keep those outside safe and offer to those inside a safety often never experienced before. Ironically enabling immense freedom and enough so that over time many questions are asked and answered.

‘Why have I killed?’ is an even more poignant question when asked by the child who has murdered. The answer often however more readily available to their adult counterparts.

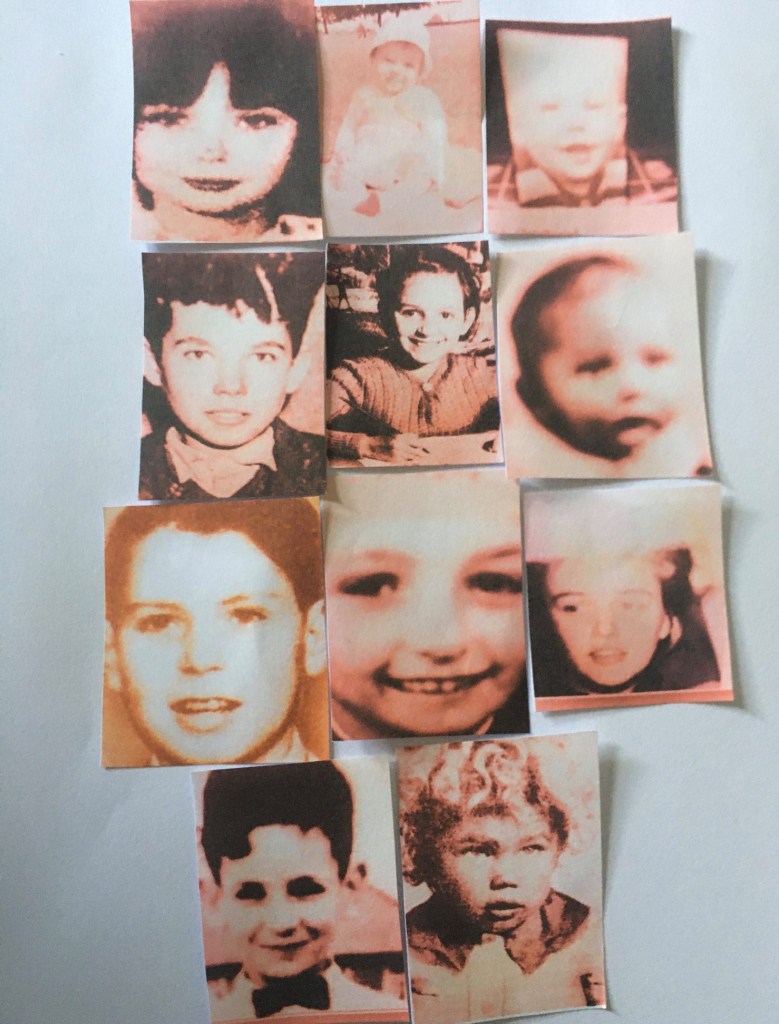

All the children in the photographs attached to this post except for one, who so far in life has managed not to murder anyone, went on to murder more than one person and some murdered many. As the photographs indicate they did not come into this world as monsters. They have arrived in the same way as you and I. Later, when they arrive in my life, it is most certainly because they have behaved monstrously. Even then, they seldom reflect what has been enacted and captured in the graphic detail of the court bundle and subsequent documentation.

Despite what many wish for and think, the reality remains, I have never met a monster, but I have met many ghosts. Fraiberg et al writing in 1975 explain such hauntings better than I;

“In every nursery there are ghosts. They are the visitors from the unremembered past of the parents the uninvited guests at the christening. Under all favourable circumstances the unfriendly and unbidden spirits are banished from the nursery and return to their subterranean dwelling place. The baby makes his own imperative claim upon parental love and, in strict analogy with the fairy tales, the bonds of love protect the child and his parents against the intruders. the malevolent ghosts. This is not to say that ghosts cannot invent mischief from their burial places. Even among families where the love bonds arc stable and strong. the intruders from the parental past may break through the magic circle in an unguarded moment. and a parent and his child may find themselves re-enacting a moment or a scene from another time with another set of characters”.

… and yes, for some, that unguarded moment of enactment is murder. When the associated ghosts manifest before me, they are often desperate to be exorcised. I guess that is also part of my job.

No wonder we are so readily entertained by the ghost stories of others, watching our own ghosts at play may be far too scary.

All this of course begs the question – Who actually is it that should be in prison?

Please let me know if you can identify the one child pictured who has not murdered anyone… yet!

Br Stephen Morris fcc